An active iNatter who has access to a restricted military / naval area among our wildflowers.

The rest of us get to a closed gate … protected wildflowers etc is a win.

I think you’re just imagining a different context than what I’ve experienced in the U.S. Trust me, we really, truly are not talking about lower human impacts, just restrictions on who is allowed to create those impacts.

Here’s a place that annoyed me recently, where a local quarry’s put a locked gate on public land (left red arrow) and bulldozed a pile of dirt across another road (right red arrow). Good thing the quarry is being protected from hunters, eh?

Work of companies will stay there, no matter what, having less additional people there helps, and definitely hunters would be a bad addition.

I don’t at present have reason to believe either that hunters have a net negative effect or that a slight change in their spatial distribution would create any meaningful effect on the landscape. Also, for what it’s worth, in some areas the private landowners who control access to public lands use that fact to their advantage by charging hunters for access and running a hunting guide business. That’s not among my objections to private control of access to public lands, though. Some of the hunting guide businesses are likely to be a net positive ecologically, because the income from hunters is replacing income from livestock grazing, which is the single biggest ecological threat in many areas of the western U.S.

I do, however, have reason to believe that the more people visit public lands, the more they care about those lands and are likely to push for better management.

Also, to be clear, my comments above are related only to the western U.S. I don’t know what’s going on in other countries. I’m guessing hunters are more of an issue where you are. You’re probably not going to convince me that they’re a major ecological threat here, though, when my experiences indicate otherwise.

I wonder how much of the land ever had public access to be blocked in the first place. I suspect much of it never had public access. That access costs money and must be acquired from private land owners. And it’s often not the previous landowner that’s the problem. They had “owner access” that transferred to the gov’t but that’s not public access. It’s the neighbors that you have to cross and the neighbors would have to sell/give public access. They may not want to.

Why can utility companies still access? Well, they have purchased access or claimed it via eminent domain (forced sale) so they can get to their equipment. Ranchers? The gov’t can lease the land and access easements usually cover lessees. Is there corruption in some of these deals? Well… there are people involved, so yes.

There are plenty of cases where the buyer gets land with no access at all. Maybe they were naive or maybe they thought they could buy it later. But now they own land that they can’t even get to. More often, they have access. It’s just very poor access. Like a 20’ corridor that only mountain goats can travel. Buyer beware.

I would wonder if all those properties have always been public or if at least some were previously privately owned but now have become public, through means such as donation, devise, seizure or forfeiture.

If they have always been public, like the beaches here in Mexico, then it is far easier to maintain access to them because the public has continuously expected access.

I also am not familiar with how you are defining public land. The beaches here are public in that they belong to all Mexicans. But there are also different types of land ownership here, such as ejidos, which are the lands that were amassed by large haciendas but now are held collectively by the state.The villages where those lands lie make their own determinations for how to distribute the rights to use the land individually. So the land is technically public, it belongs to the people, but access is not available to all people because ejidos are part of the agrarian reformation. Nor would anyone here expect to be able to access that land, though, who was not a part of that particular village.

Lots of good observations here. It seems that globally there are similar factors of wildlife protection, varying human impacts, and varying levels of access to public lands, but the interplay can be quite different. We all seem to agree that access to public land can have good and bad aspects. That balance changes from place to place.

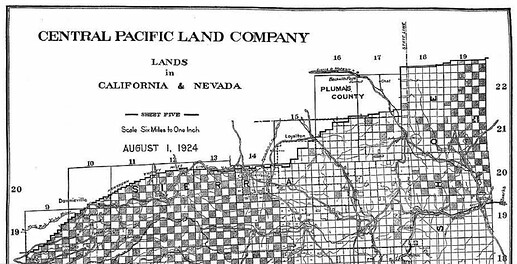

Going back to the western United States, one big factor in creating these inaccessible lands was the intentional checkerboard division of the landscape during the 1860s when alternating square-mile sections were given away to railroad companies, with the federal government retaining the remainder. Here’s an example:

(source: http://cprr.org/Museum/Maps/CP_Land_Map_1924.html)

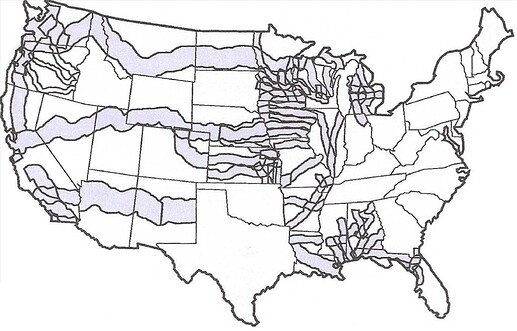

These land grants covered 10% of the area of the United States and gave the railroads effective control over about a third of the nation’s land (the shaded areas below).

@aspidoscelis’s point about distributing hunting pressure across a greater area is interesting. It does seem true that making these enclaves accessible would mostly transfer hunting impacts from place to place, as it won’t change the number of hunters or their available time. For more common species, that probably would mean more evenly distributed hunting pressure. But it seems it could also transfer hunting pressure from more common species to more threatened ones if it opens up areas that have been a partial refuge for these species.

There are lots of other threats to wildlife on public lands in the West, such as grazing, logging, mining, climate change, intense wildfires after a century of fire suppression, etc. For a lot of species in many places, hunting poses less of a threat than these. I support a better process to open up inaccessible public land. I’m just suggesting that it should include assessment of the likely impacts and some measures to mitigate those.

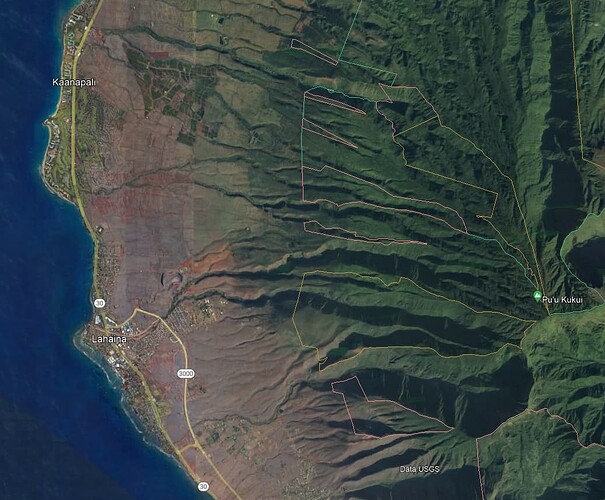

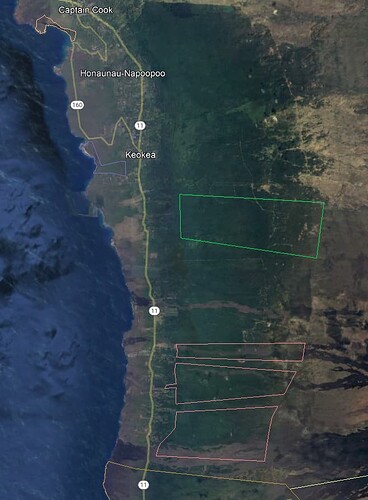

That’s actually a place with good access. You can drive right to the forest reserve, and there are numerous trails within it, including the one to the summit. I’m thinking more about Maui and the Big Island, where the reserves are completely landlocked. In some cases there are access agreements for state workers to go in via private roads, but for others there’s none and the only access is by helicopter.

In my area (Oregon) essentially all the public land has had public access for timber harvest and/or grazing. There are roads to much of it, though sometimes they’re in bad repair.

Oh, yes. The best prairie remnants in western Washington are at Ft. Lewis between heavily built-up Olympia and Tacoma. Some of the best is on the artillery range. A TNC botanist who studied the place reported that the only management change he recommended was to target the trees coming up out there. Significant parts of the prairie were fine. (Not all; invasion by Agrostis capillaris.)

You’ve hit on a big part of the problem here. Private land owners who control access to public lands can limit or prevent access to public land and by default become the gatekeepers for that land. They get to decide who can hunt/fish/photograph or study on that land. A few years ago we had a case in Canada where a very wealthy foreign land owner who owned a private ranch blocked access to a public lake. After several lawsuits he won and public access was lost. Who gets to fish there now? I’m guessing his wealthy buddies.

I agree with the first half of that sentence but not its parenthetical addendum. :-)

I would bet that most of the people who own the private land that blocks access to public land are hunters, to greater and lesser extents. Some of them, as mentioned above, use their control of access to public land (and of access to the private lands they own) as the basis of a commercial hunting guide enterprise. Some states specifically grant hunting tags on the basis of private land ownership, too, though I don’t really understand how that system works.

Agreed entirely on that.

I’m very skeptical of the idea that restricting public access is likely to have a net benefit over the western U.S. as a whole, though I think it probably can have benefits in particular areas. Part of my skepticism is that this seems to entail, in effect if not in intent, a claim that privatization has inherent ecological benefits. We are, after all, talking about de facto partial privatization of public lands. There probably are contexts in which privatization has ecological benefits, but that this is generally the case seems like an extraordinary claim requiring extraordinary evidence, to me.

For instance, in the DOD lands mentioned above… at least where I am familiar with the situation, they’re not in unusually good ecological condition because hunters or recreational users are excluded (the biggest DOD land near me, as it happens, is open to hunting, with various limitations), but because ranching, logging, oil & gas, mining, and various putatively beneficial actions of land management agencies are excluded.

A bit of a hoo-ha in UK at the moment after someone bought a large part of Dartmoor National Park - where there has long been a unique (in England) local law understood to permit wild camping without the permission of any landowner - and decided to fight that law in the courts. Unfortunately they won. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-64333066. Thankfully most landowners seem to want that practise to continue in some form, but they now have much more control over the terms. Hopefully the decision will be appealed and overturned. Not a denial of access, but a restriction of activity.

There is lot of “public land” here that is state owned; and it has miles of dirt access roads but the roads are gated at the main paved road entry points. These gates are only open during hunt season, for hunters. It is a point of contention among outdoor enthusiasts - why are hunters getting easy access to use it, but not hikers or other outdoor enthusiasts? Often who don’t want to go during hunting season - but when else do we have access? Why are hunters so special that they get access rights others don’t?! I will note deer act invasively here, they are severely overpopulated and the lack of hunting (lot less than in history) and lack of predators to go after them as well has caused issue. There is a lot of catering to deer hunting I believe partly for this reason - to encourage it! (In fact, a fair few food kitchens/homeless shelters/etc will take deer - encouraging hunters who don’t want the meat to donate their hunt!) But…that doesn’t explain why the roads are not open during non-hunt season for non-hunters.

A neighboring state actually had a big to-do about this, and I believe it won, allowing hikers and bird watchers etc equal access year round.

Another neighboring state changed licensing so you just purchase an access license and then hunting license additionally - they just turned it into a make more money thing haaaaa (luckily I think it’s only like $30 for an annual pass - it’s vehicle based not per person).

Technically here you could go, but with the access gates closed to drive in, you may have a long hike to get to where you want to be whereas hunters could just drive there because the gates are opened for them! And that’s the issue - unequal access that favors hunters only.

For what it’s worth, I think it’s pretty much universal that lands owned by a state have more restrictive access rules than lands owned by the federal government (Department of Defense excluded). That’s certainly the case for Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico, the states I’m familiar enough with to be certain off the top of my head.

I’ve noticed that too…I’m more familiar with the southeast…that’s interesting though.

We have the largest wilderness area east of the mississippi; and regionally a lot of huge national forests, access has always been excellent in these places…

Let us also mention DOE lands. There are reasons why the Forest Service has a research station inside the Savannah River Site. Here is just one beautiful scene out of many.

It is land belonging to government agencies: mostly Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management. After the land was seized from the Native people, it was held by the federal government, and portions were granted out to homesteaders and the like during westward expansion. The portions not granted out became the lands managed by these agencies.

when i have seen this, it’s usually because fees or taxes oriented towards hunters paid for the purchase of maintenance of the land. I agree everyone should be able to access, but there’s also a logic to it.

I disagree with others that here in the US hunting is causing ecological impact. At most, it’s neutral from an ecological standpoint. In many areas it is helpful as with deer in the eastern USA. There are many reasons one might not like hunting, but in terms of ecological impact in the united states (which seems to be what most of this thread is discussing) i don’t see much impact. Same with trapping, which people like even less.

I can’t speak for other countries, it certainly sounds like in some parts of the world, maybe most, hunting can cause negative impacts.

11 posts were split to a new topic: The ecological impact of hunting